How to Rewild Your Outdoor Sleeping

A few years ago I had a strange fascination with sleeping outside. I wanted to find a way to make my camping experience better. I didn’t like how everything seemed like a compromise to make gear light weight and utilitarian. I wanted to adapt my body to the wild outdoors so that I was actually living and not camping. That meant being at home and at ease in all different circumstances: rain, snow, summer and everything in between. “Camping” implies compromise, temporary, portable, just getting by. I wanted to consider my expeditions as “living” outdoors rather than camping. It just made sense because nature has all the elements for sleep. The relaxing effects of grounding and Shumann’s Frequency, the exercise and the sun and fresh air and away from everyday duties. But what is essentially different as far as sleeping and why do people idealize their ‘own bed’ as the most comfortable place to sleep? I started looking at what are the places that camping gear is causing discomfort or compromise in what would be a more sensuous experience.

Synthetics gear was a roadblock. I had become sick with Multiple Chemical Sensitivities and could no longer use my toxic-covered-in-chemicals modern camping gear. I had to figure out a new way. The following two years I figured out how to sew and invented a wool sleeping bag and organic canvas tent. I slept most nights outdoors because I was trying to understand the dynamics of how to live in the cold. I know…it sounds crazy. But I was fascinated with how this new sleeping arrangement was affecting me. I would go on wilderness excursions taking my rag tag natural gear prototypes (I had barely learned to sew) and spend a few days doing what came to be known as Forest Bathing. Forest Bathing is when we go there for rejuvenation and sensory experience rather than with the focus being on accomplishmen

The tarp can be pitched 4 feet high, 3 feet high, or 2 feet high depending on the weather conditions. Pitching lower during wind is essential. The poles are fallen limbs found on the spot.

How I discovered the healing power of natural fibers combined with living outdoors.

The first and biggest elephant in the closet is the fact that the clothing, tents and sleeping bags are synthetic. This has come about in the past 30 years due to the rising tide of the synthetic fiber industry. Slowly old traditional fabrics such as cotton and wool have been replaced with nylon and polyester variations. When we zip ourselves up inside a synthetic sleeping bag (even down fill uses synthetic fiber) and inside a synthetic tent, (and usually wearing synthetic clothing), we have effectively wrapped ourselves in three layers of plastic. And yet, you will find few alternatives for lightweight backpacking and camping in the outdoor stores.

Toxic chemicals with potential health and environmental impacts are widely used in the manufacture of outdoor clothing and gear, according to a Greenpeace study.

Chemicals such as perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) are used to make moisture-wicking and water-repellent equipment, including jackets, pants, sleeping bags, boots, and tents. The compounds help keep campers and hikers dry and dirt-free, but they are hazardous to the environment and human health, Greenpeace says. The chemicals are also widely used in common household items such as nonstick cooking pans and fire-retardant foam.

The relaxing effect of the Shumann’s Resonance which is the Earth’s Magnetic Frequency or sometimes called the Earth’s Heartbeat is built into the DNA of all living beings on the planet. The same 7.83 Hz. which is the Shumann’s Resonance is the same as Alpha Brain Waves as well as the frequency of Infra Red Radiation. All life uses this frequency as a fixed reference point to set the circadian clock. Modern living (surrounded by non-native Electromagnetic Fields and lighting) interrupts our connection to this and this throws our circadian rhythms off. When we can’t ground to the earth through the Shumann’s Frequency the first thing that goes is sleep. What people haven’t realized is, synthetic fabrics throw this off.

In addition to the toxic chemicals, there is another way synthetic fabrics create a state of inflammation in the body. Because they contain metals (built into the petroleum molecule) they disrupt the subtle electrical current running along our skin called Peizo Electricity. This essentially ungrounds us and causes us to loose electrons (which is the same as cellular energy).

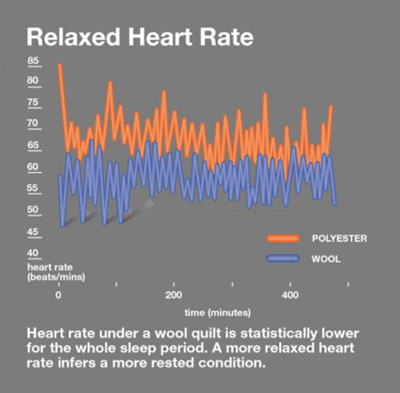

Secondly, due to the fact they trap moisture and heat next to the skin, the heart has to pump faster in an effort to adjust body temperature. When the heart beats significantly faster, the sleep cycle is interrupted because the brain waves cannot relax into their natural pattern. The result is waking up not feeling fully refreshed, because you didn’t experience the full sleep cycle. Most people attribute this to the fact they are camping and not in their own comfortable bed they are used to.

The third way synthetics cut us off from nature is the tent. When sealed up in a plastic tent we are cut off from the fresh air full of all the aroma’s of the trees, flowers, negative ions from the mist of the creeks and that forming in the air from dew, fog, rain. These healing and sensuous aspects of nature…part of the reason we are going out in nature in the first place. Add to that, the sealed up synthetic tent also traps your own body’s moisture inside (we release 2 liters per night in breath and insensible perspiration).

The forest, prairie or desert air is healing, so a tent or tarp that allows us to experience it fully will provide the best sleep. Indeed, research shows that trees really do have healing powers. For one thing, they release antimicrobial essential oils, called phytoncides, that protect trees from germs and have a host of health benefits for people. The oils boost mood and immune system function; reduce blood pressure, heart rate, stress, anxiety, and confusion; improve sleep and creativity; and may even help fight cancer and depression. These and other impressive benefits of forest medicine are catalogued by physician Qing Li, chairman of the Japanese Society for Forest Medicine, in his book Forest Bathing. Add to that the negative ions from mist, dew, and moving water and there are more reasons to rethink the tent design.

Moisture Wicking Fabrics

Let’s look at the actual definition of moisture wicking

Polyester and Nylon are water resistant because they are made from materials with a particular chemistry that is similar to plastic. Instead of the water being absorbed by the fibre it sits in droplets on the fibre’s surface and moves around the fabric by running along the weave. Eventually, the water droplets reach the outside of the fabric where, if exposed to the air, they evaporate. Because the wicking material does not absorb moisture, the fabric will dry faster.

The dark side of this process is that these fabrics which wick moisture also hold moisture next to the skin (think plastic bag). The skin is somewhat suffocating because it is surrounded by plastic…a non-breathable material. The process causes the body to struggle in its moisture and heat regulation efforts.

But the real dilimna is even though the fabric can wick moisture, it doesn’t make you necessarily dry. The ideal situation would be to have a fabric that is both MOISTURE WICKING as well as BREATHABLE. Breathable fabric is that which lets moisture pass through it. Yes this seems like a contradiction. How can you let moisture pass through the fabric AND have the fabric keep you warm and dry?

Wool is truly moisture wicking as well as breathable.

Not only can wool wick sweat from the wearer, wool can move water vapor before it even turns to sweat! Wool is able to release moisture, not just through holes in the fabric, but through the fibers of the fabric itself.

Wool uses a process called “heat of sorption” to absorb and release moisture. As wool absorbs moisture from the atmosphere a natural chemical process in the wool releases heat, warming the wearer. In cold weather the natural crimp in wool fibers creates tiny pockets of trapped warm air that act as insulators, holding in heat next to the body. This same process has a cooling effect in warm weather, as wool releases moisture it absorbs heat from the wearer and the tiny pockets of air created by the crimp in the fiber trap cool air and insulate the wearer from warmer outside temperatures. As wool pull moisture away from your skin to evaporate you feel cool and dry even in hot weather.

What about the Tent?

So besides the clothing and bedding, the other piece of synthetic gear needing fixing was the tent. The problem with the tent is actually similar to that of the sleeping bag. The tent 1) Holds your body’s perspiration in making the air damp and clammy and 2) Keeps the fresh rejuvenating air out. The tent alternative I designed was a six pound beeswax coated canvas. This tent allows air to pass through it both ways. So it will release moisture from the body and it will allow fresh air inside. It is very strange almost magic-like how the rain will penetrate through the surface but not fall down. You can see the water flowing down the inside of the tent but you still don’t get wet! This was okay for a little forest bathing but not practical for actual backpacking because it becomes extremely heavy when wet. So I found out about Ray Jardine who was an early pioneer of Lightweight Backpacking and author of Trail Life. I made a “Ray’s Way” backpacking tarp. (shown above). He has the same idea as me that closed tents are not good for the same reasons (lack of ventilation). His tarp design (which is from an old time design originally made from canvas) is open on each end and optionally open on the sides depending on how you pitch it. Jardine’s philosophy is that moisture from the body should be allowed to escape by this kind of ventilation. He believes comfort and temperature regulation is best had by having some wind and air pushing through the tent/tarp than to seal everything up. He also, like me, likes the feeling of being connected to the surroundings rather than zipped up and sealed off.

The places I still use synthetic in backpacking are:

1) Poncho and Ground cloth

2) Tarp

3) Closed cell foam sleeping pad

4) Waterproof liner for backpack

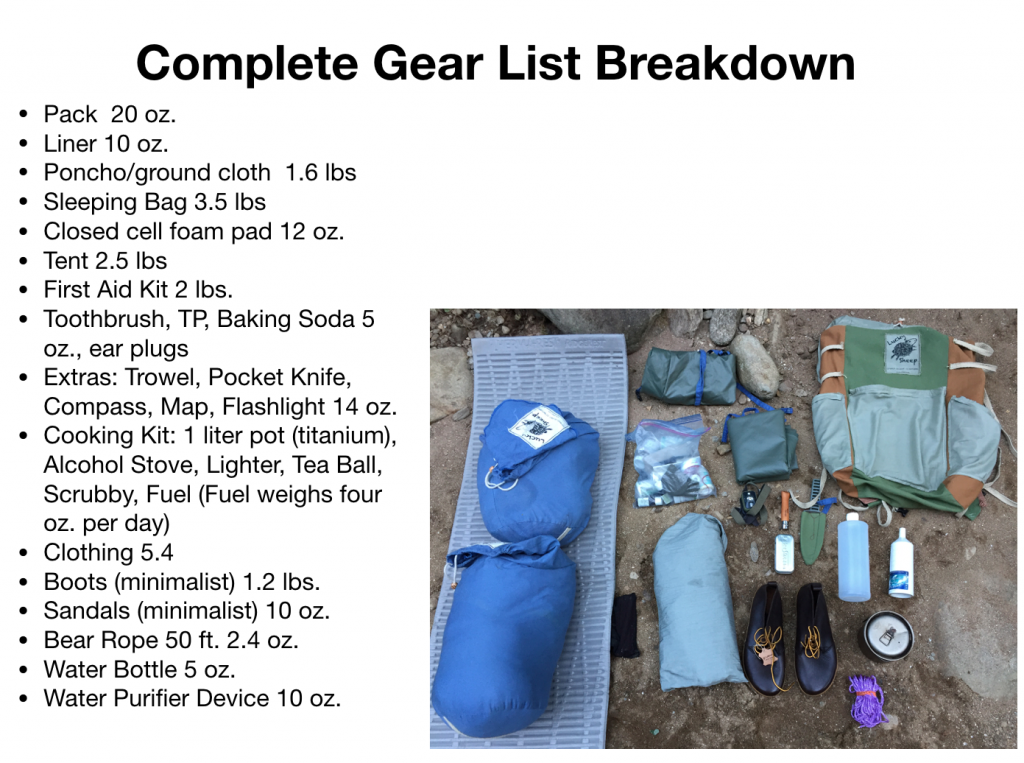

My total pack weight before food and water is 21 pounds. I take about 2 lbs. per day of food.

Why Haven’t People Noticed this Before?

Paul Petold founder of NOLS, Outward Bound, and Wilderness Education Association teaching in c. 1970s. Notice the gear…wool base layer and insulation layer and tight woven cotton wind shells. Before the advent of synthetic outdoor gear.

In college I was an Outdoor Recreation Major and took numerous outdoor leadership training courses including one taught by Paul Petzholdt founder of Wilderness Education Association (WEA) in 1983. I started out using some wool in the early days of my Outdoor Leadership journey.

Paul Petzholt was a big advocate of wool sweaters and socks and in the 1980’s wool sweaters were everywhere. You could find them for a couple dollars in the thrift stores. There was no alternative at the time shortly before the advent of polar fleece and pile jackets.

For decades since the 1970s there was an all out effort by the outdoor gear industry to convert clothing, tents, sleeping bags, etcetera into new lighter versions using synthetic fibers. For a time even wool socks were difficult to find. Everything from the Base Layer (underwear) to the Insulation Layer to the Shell Layer became synthetic as the only option.

Part of the reason seems to be at that time they hadn’t invented a wool base layer. Finely woven woolen merino fabric wasn’t invented back then. Base layers were usually cotton, which is notorious for absorbing water and being slow to dry. So everyone had a phobia to cotton for good reason. Who wants to wear water logged heavy clothing and thus be prone to hypothermia.

I was following the standard modern outdoor gear dictates before I discovered the benefits of Organic Camping.

Then in about the late 1990’s a new version of wool sock was introduced to the market. This wool had been around all along but for some reason had not been discovered. The brand name “Smart Wool” made it seem like some kind of new thing had been invented. However it was really the first use of merino wool in the outdoor industry. Merino wool is the wool from the merino breed of sheep which produces a softer feeling wool which doesn’t have the itch associated with most other wool types.

This was a game changer. Eventually other merino wool products started popping up like base layers, tee shirts and sweaters.

But there was a point I personally didn’t have a stitch of wool or natural fiber in my outdoor gear. And at this time some new research started coming out about the benefits of sleeping with wool. I changed my indoor sleep environment into wool and my sleep was completely altered. I started sleeping, with no heat in the house, in the dead of winter under a wool comforter and would wake up feeling warm and refreshed. In contrast to when I used my winter synthetic sleeping bag and even with blankets on top of it…never could I feel that warm glowing feeling I got from the wool comforter.

So my next question was: How can I bring this outdoors? Something really didn’t seem right. Here I was getting rid of plastic in my home, and yet when I go in nature plastic is all I bring. At first it was merely a psychological and perhaps moral (ecological) riff. But this new discovery and research was bringing it into a quality of life issue.

This prompted me on the five year quest to invent and test the wool sleeping bag design which turned into the first lightweight wool sleeping bag on the market—Lucky Sheep™.

https://qz.com/1208959/japanese-forest-medicine-is-the-art-of-using-nature-to-heal-yourself-wherever-you-are/

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]