There is nothing like waking up to the forest as my house, deep down close to the bossom of Mother Earth, in the quiet, still pounding of the soft heartbeat, where I can hear my own presence merging with that of the whole of nature.

As I sat on the side of the mountain watching the sun in the early morning, I was so deeply present with my life and feeling into the future in that magical neutral place where I can listen to inner guidance. I was holding the excitement and beauty of moving back into my tipi and yet, holding the magic of my friends and community in the city. How amazing these beautiful people have effected my life and allowed me to grow and blossom. And yet, for now, I was feeling so welcome and so whole out here alone in the exquisite forest sunlight whispering sweet words into my ears.

The reasons to be in a tipi or not be in a tipi are not such a big deal,since it is a nomadic dwelling and easy to move into or out of at any time, or move it to a new location however temporary. Looking at the tipi from the outside when not living in it and thinking about what it would be like, and from the inside, when I am actually doing it, I get amazing insights into the whole paradigm of Western Civilization. I believe I have discovered some things that can be discovered in no other way. Thinking outside the box while living inside the box is impossible. In fact, I see my whole ‘tipi quest’ as an experiment in minimalist design, and I see myself as a walking think-tank. In my case, I think with my heart and soul as well as my head. I test my ideas with my body and I use instincts and intuition to guide me.

The first phase of my tipi living experiment lasted about a year. During that time I was in and out of it as I was learning how to work it, manage it, live in it, adapt to the new reality of extreme minimalism and some times austere asceticism.

My tipi needed some major maintenance and repair, which became apparent in heavy rains, so I moved back “indoors” that is, a house built of more solid materials with modern appliances and running water, and surrounded by a city with cell phone towers and stores and cars.

Going into the tipi without all the systems in place can be extremely inefficient compared to the modern setting. I had been loosing time at work so I needed to catch up on that and in my spare time worked away perfecting my tipi structure and systems for the day I would move back into it.

During this tipi ‘down’ time I also continued backpacking excursions into the Nantahala and Pisgua National Forests and Great Smokey Mountains National Park. During these adventures, I used a tiny tipi I designed and constructed myself as a backpacking tent. It is just big enough to hold me and my gear and weighs about seven pounds when dry. I daydreamed and fantasized about getting back to the earth and living with the sun and stars and icy cold waters of the mountain creeks and rivers which were bringing back a vitality I had never known. It was an intense and busy time between work, tipi repair, and backpacking adventures.

My friends and business associates seemed to be worried for me–and for them–that I might not come back from one of my trips. I might go completely wild and become feral or something.

I have to admit, I thought about that more than once. And, the call of the wild was so strong, I wasn’t sure why I went back to the city sometimes. I think it boils down to the fact I have not learned how to hunt and feed myself yet. And also, I think I don’t have a village to go with me into the wilds. So far, I have always come back into civilization to be with with the rest of the crowd.

It’s not at all that I don’t like people. It’s just that the modern lifestyle feels foreign and alienating to me. And it’s not at all about survival or lack of motivation. I see the modern setting as survival and has been built up due to humanity’s collective fear of nature—to protect us from the sabor tooth tigers and Tasmanian devils. Remove the fear of nature and inability to live comfortably in the elements and suddenly the whole world is seen in reverse of the assumptions and paradigms that have been handed down to us from the time we were born.

It just seems to me that the tail is wagging the dog. At least for me in my life. Work inside a box, think inside a box, live inside a box, so I can buy modern things which are all made inside boxes. If I could make my own things from nature, the IRS would probably come after me to put me back inside a box. What a mess!

I think we have it inside out. And I see the tipi as basically reversing the design elements of the modern abode. You are putting nature back into your life, keeping it at just the right amount of distance so you can both be a part of it and be comfortable at the same time. You are saying ‘yes’ to life, not pushing the beauty out. You don’t need to hang things on the wall to replace what you have moved away from. Your life is art. You can hear music all the time. You can feel, you can relax. There is nothing to be afraid of.

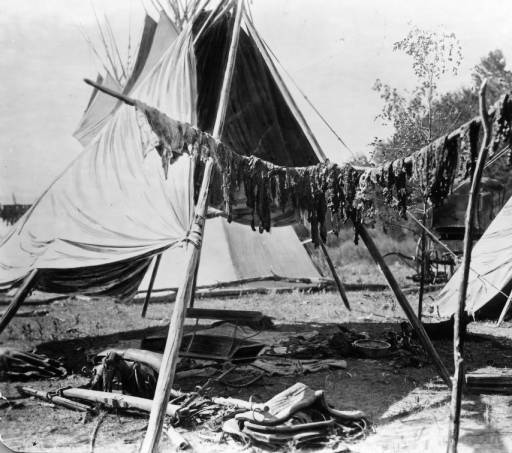

Some of the challenges were simple things like knowing when the wind would pick it up and knock it over and how to prevent that. If the Plains Indians could live in them, withstanding 90 mph winds in the cold north, I knew there was a way.

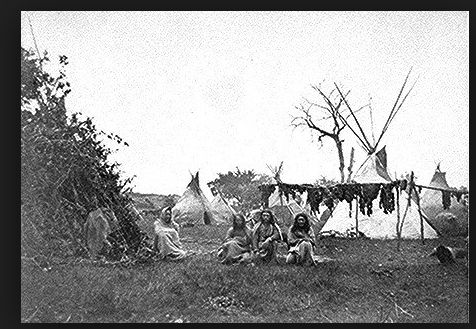

I would continue to seek out tipi experts and information as my quest for the ultimate outdoor experience continued. There had to be a way to unite the two worlds of modern and Paleolithic. And fortunately I am not alone. There is a thriving global community of people thinking very much like I am, bored or tired of modern technology/society and re-creating and re-learning the ways of our ancestors.

This was not about survival. My hypothesis was, living in a tipi could be comfortable and even luxurious if it was done correctly. I wanted to live right up against nature and the elements and was not attempting to escape from responsibilities. This was a most rich and amazing experience. I wanted to continue my office job INSIDE my tipi. Maybe some day I would go completely wild but that wasn’t really necessary right now. I was most interested in finding a bridge between the primordial Paleolithic world and the modern and trying to merge the best of each.

Tipi as shelter. It’s more of an escape from shelter. When shelter becomes numbing, cutting me off from the things I want to experience. I want the wind, rain, sun sweet breezes, birds. I WANT it. Tipi is not the best SHELTER as far as protecting from the environment. There are better, easier things out there. What tipi is…a doorway into the earth. It is a way to experience our primal environment without being crushed by it. It is a way to tap into primordial instincts that lay dormant. Tipi is a shelter from industrial society. It is a way to find wildness that will open the heart and soul to a new dimension. Tipi provides access to an unexplored frontier. It cannot be experienced with something else because this is FULL BODY immersion into a sensual realm.

The fire in the center of the tipi is the ritual center of the universe according to Plains Indian culture. To me this is speaking the true nature of abundance and the fact that PRESENCE–that you can be at HOME wherever you are–resides within us. I found this quote by Black Elk that speaks to this. The Sunset–spoken by Black Elk

“Then I was standing on the highest mountain of them all, and round about beneath me was the whole hoop of the world. And while I stood there I saw more than I can tell and I understood more than I saw; for I was seeing in a sacred manner the shapes of all things in the spirit, and the shape of all shapes as they must live together like one being.And I say the sacred hoop of my people was one of the many hoops that made one circle, wide as daylight and as starlight, and in the center grew one mighty flowering tree to shelter all the children of one mother and one father. And I saw that it was holy…”

Any more protection and you aren’t out there anymore. Living in a tipi is like being outside, kind of like wearing a jacket. You don’t really go indoors. You are always outdoors. You have just enough protection from the elements to maintain homeostasis. You can hear everything, you can feel the mist and the cold. The wind rattles the canvas and the poles shift. The rain comes right in, dripping down the poles and falling through the smoke hole. You realize, rain and cold and wind are not a problem. The ground becomes your friend. It’s not that big monster that everyone protected you from your whole life. Not a problem.

Lesser forms of shelter can provide survival, such as a backpacking tent or a debris hut made from sticks and leaves. But a tipi provides a HOME.

I experimented with different ideas for the floor, storage systems, sleeping platforms. When it comes to food prep, the tipi felt lacking. Running water is certainly a system. I mean, there are times I felt like I just wanted to get the job done and there were times I felt lke being present with nature. Not trying to make the tipi into something it isn’t Not trying to really defend the tipi as a place for lvigin the modern life. Things that didn’t work very well were storage of papers and electronics. I did do it though. I kept my papers and books in airtight plastic tubs. I kept my laptop computer in a waterproof dry-bag used for canoeing. Clothese I had to make a choice between trapping moisture IN and letting it dry out when there was a dry spell. When I added the fire to the tipi, I realized that was what made it really sing. Now I had a tool for bringing in the element of dryness even in any weather condition.

About 10 years ago I had a near death experience wandering in the dark forest during a snowstorm and loosing my way back. Two parts of me compete for my attention: the social dude that needs to make it in the world of people and career, and the wild man that needs to survive in the wilderness and learn the language of nature and poetry. The wild man alter ego was trying to kill me with a knife–in a dream the night before I got lost on the mountain–for not honoring that side of myself. I made it back home miraculously, almost falling down a waterfall. But only way to proceed was to honor the wild man soul side that wasn’t getting the nourishment. Living in tipi is slowly thawing out that side I thought I couldn’t have. Still a challenge. Plus social perceptions and the fact I raise the fears of people who project onto me things that I think are group consciousness fears that I am challenging within myself. Interesting to see and feel what is me and what is group consciousness. But it all goes towards the goal of the question: “who am I?” that we each can ask ourselves every day. And the answer is not about our house or our car or our accomplishments. Take those out of the picture and then ask yourself that question. That’s what I do, and that’s why I am getting more and more fluid. Hey someone has to do it. It’s really scary. So I know I was put here to take this path. How to stand in my power and not let the winds of other people’s thoughts and fears blow me over. But also how to know when I do need to listen and someone really does have a message for me.

Am I homeless? Was I mistakenly born in the wrong era? Do I just want to be different? These are questions I’ve asked myself. But what I know from deep inner exploring, I am really a bridge between the modern world and primordial nature. I can travel between the two. It’s kinda like two dimensions. I almost feel like I shape shift of something. So for this thing they call “Nature Deficit” that people are experiencing, I have a way to solve it. I know how to open the door .

So far I had solved several of the design challenges. They needed to be approached with a very conscious paradigm or hypothesis–The body is the real abode. In other words, the body can handle itself in nature given it’s natural advantages, which are, ironically, the original conditions of human existence. This is the OPPOSITE of the current archetectural paradigm that is so engrained in design and society that it is never mentioned–that paradigm is that NATURE is a dangerous place and we must live our lives away from it, inside protective boxes.

People ask me, “Why did you ride your bike? Don’t you have a car?” and “Don’t you have an umbrella or rain jacket? You are soaking wet!” I can see we are coming from entirely different places. To me, the bicycle is a privaledge and luxury. To feel the wind and move my legs and get air in my lungs and to meet people face to face in the community and see what the clouds are doing. It makes me feel alive! And the rain. I want to FEEL the rain. I want to BE the rain. At one time I asked myself “Why am I wearing a rain jacket? What’s a little water? What’s a little shivering? and when I realized, the jacket was keeping me from a deeper experience. I stopped wearing it. And then I asked the same thing about a house, and you can see where that has lead.

The more I tested my hypothesis, the more I found it to be proving itself valid (I.E. barefoot walking, sleeping on hard surfaces, Paleolithic Diet). So far, the Paleo Diet and Fitness movement was way behind. They have not even gotten their feet wet in the cold mountain streams that I have been diving into.

I am using the human body as the basic design element. Whatever was good for it, was supportive of this new outdoor life. That means, for example, synthetic fabric was out, because it disrupts the body’s electrical system and therefore actually doesn’t perform as well as wool, silk, and buckskin. I needed to construct a material culture made from all natural ingredients like wood, stone, bone, cotton, wool, sinew, leather and beeswax as much as possible. If I couldn’t figure it out with those materials, I would make a few exceptions. See The Soul of Design.

And, anyone who tries what I have tried will very quickly find out, food cravings and tastes get completely altered. You get so hungry and the only foods that work are Paleo. You cannot waste any energy on empty calories or foods which don’t generate warmth. Fat, fat and more fat, with some protein mixed in. Basically, pemmican does the trick, and the Native Americans figured that one out maybe thousands of years ago. I find myself knocking on the door of the ancient ones for the answers, sometimes a little more than is close for comfort. See Ancient Ghosts on Haskell Indian College Campus. The modern world has all but forgotten and could care less.

Heat— The fact is…that nobody seemed to get when I told them…is that the tipi is one of the warmest and most comfortable houses I have lived in. It is extremely easy to keep warm and real warm. One little fire would last for hours. An open fire works, but a tiny woodstove adds just the right amount of modern technology for my needs. You just build the fire and close the door and there’s evenly distributed slow heat for and hour and then you open the door and throw a couple more sticks in.

But more importantly than the fire, is the fact that the human body can adapt to the cold to the point the perception of cold is completely altered. This practice is scientifically proven and extensively documented in a phenomenon called “The Cold Pathway” or “Cold Thermogenesis” which has been promoted in the Paleolithic Movement, mostly by neurosergeon Dr. Jack Kruse, for the past couple of years. Basically the cold stimulates metabolism and supercharges the immune system. This whole tipi experiment is actually testing a number of factors known to establish supreme robust health and vitality. These factors can all be found under “Circadian Biology” and in a nutshell are the very things we would have if we took modern technology out of our lives:

1—Diet: eating what is available in one’s climate as it is in season. Grains are completely out. They were not around during Paleolithic times (pre-civilization)–most of the 1.5 million years of human evolution. In a cold climate, carbohydrates do not grow, or are not ripe during the winter. See this blog post on Indian Pemmican recipes.

2—Night and Day Cycles: exposure to the daylight, or lack of it, synchronizes the biological clock to produce optimal hormones for building, repair and maintenance. Melatonin saving eyewear is a bandaid that helps when exposed to artificial light.

3—Exposure to the Shumann’s Resonance or Earth’s Magnetic Field Frequency of 7.83 Hurtz, Earthing, Grounding, barefoot walking, etc. See Getting the Sleep of Your Dreams by Optimtimizing Circadian Rhythms.

4—Temperature. Being exposed to the elements. This also works in unison with the other three factors or dimensions of Circadian Biology to synchronize timing of neurological signals that power the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system.

Rain—Tipi’s were traditionally used in more arid climates than the one I live in, which is the temperate rainforests of the American Southeast Appalacian Mountains. Actually, this just supports my experiment even more, because if I can make it work where I’m at, the tipi is even more adaptable and versatile. While humidity would ruin many things and is an inconvenience, it also happens to be an extremely healthy thing in some cases, generating supercharged negative ions, like those found next to a waterfall or after a rain. What seems to work best is keeping some things like clothing in wire mesh baskets so they can breath, and keeping other things, like papers and electronics sealed in waterproof containers. Another trick is to periodically light a fire during the warmer months solely to dry things out. During the rainy season, this means once per day. I find this to work very well with doing a cold swim right before–it’s like having a sweat lodge. I look forward to taking my tipi out west sometime to enjoy the ultimate tipi climate.

The fabric needs to be high quality boat shrunk canvas which is also called ‘Marine Cloth’. Other stronger fabrics are available but they have chemicals added for waterproofing and fire-resistance which go against my principles. My tipi was leaking through the fabric which is the main reason I had to move out. I have since spent hours coating it with beeswax, which was the traditional practice in the old days, and that did the trick. One also needs to erect the tipi properly, which takes skill and practice, but is easily learned. Managing the smoke flaps to allow smoke to escape without too much rain coming in. Tipi poles need to be smooth because water actually drips down them, by design, and any bump can cause a drip.

Bedding and clothing, there is only one choice: WOOL. it is magical in several ways by keeping a person warm even when wet. Wool is hard to come by in this age, so I ended up designing and constucting a lot of my own belongings.

Food prep/running water—This will be described in detail in another article. Basically I am using the Native American practice of Pemmican—which is dried and pounded meat mixed with dried and pounded berries and nuts and fat. It is amazingly delicious and extremely convenient and efficient. You can read my blog post here with my recipe.

Lighting: very simple. Combination of high quality backpacking flashlight with amber light and adjustable intensity beam for close up light, and beeswax candles in jars for mood lighting. One candle lights the whole tipi but I like two. The tipi glows like a jack-o-lantern from the outside!

Downscaling Belongings using Feng Shui, Backpacking Philosophy and Lean Manufacturing Systems.

Categorize your belongings. Make a written list of what you own. (divide and conqour)

This is a fun excersize, to get belongings down to the bare minimum. It may seem austere but it actually can really improve personal effectiveness and organization, even if not living in a tipi. I found that it improved my quality of life, even though i would not have done it just for that purpose. And fortunately I am not alone in this quest to reduce personal belongings to the rock bottom minimum. There is a movement sometimes called the “100 Things Challenge” which basically has the same idea. It now has a book and TED talk to go with it. Look at what you own and get it down to practically nothing. The trick is to categorize and list everything you own on paper. Then you see what you really need and what is wasting space. This has material and spiritual benefits and actually is highly regarded in the ancient Chinese practice of Feng Shui.

Before moving into the tipi I downscaled to tipi-sized belongings and found myself fitting very comfortably inside a small room and without feeling any lack. The idea was to create a nomadic lifestyle that could be picked up and moved in one carload and set up without disrupting any systems. I could move locations and still know exactly where my socks are and find a pen and a piece of paper or whatever as if I had not moved.

I found myself getting to places on time, getting more done quicker, having more free time for adventures. I could now find anything I owned in no time, and my clothes were always cleaned and put away–REALLY. In this kind of minimalism, things need to be put away because there is no room for clutter. Any object will stick out if it’s not in it’s place…you would trip over it.

And, after a decade of trying to resolve the problem of needing wilderness and society each in my life in large amounts–two oppossing factors–I had evolved a completely new lifestyle full of knowledge and techniques of traveling with ease and being in different places almost constantly. Like a turtle, I developed a system for bringing my home with me whereever I go. And It wasn’t about staying in hotels or other people’s couches. It was about being completely autonomous and self reliant with my own food, shelter, and other needs. Because the wilderness was my home, and I liked to visit and hand pick parts of society that I like.

I found ways to camp either in friend’s yards or in a nearby natural area. I became something of an archiological relic. A human being who grew up in Western Society but choose to live on the fringes while being a highly effective member of the club. A person who refused to believe the dominant paradigm and to buy the current idiology of the times–especially in regards to the proper way to live. A person who saw the lies handed down to us in the history books which also shaped the way we think about things. A person who saw the contradictions woven into the fabric of society and started to pick them apart, using the same systems theory that created the fabric in the first place.

“Go to the place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.”

Frederick Buechner